Happy New Year! I spoke with Glen Hunt on BBC Radio Lancashire this morning about what the Universe (and our exploration of it) might have in store for us this year. It certainly looks like it will be an exciting year for space exploration, and there are many potential discoveries that could be on the cards. Here are some things I’m particularly looking forward to.

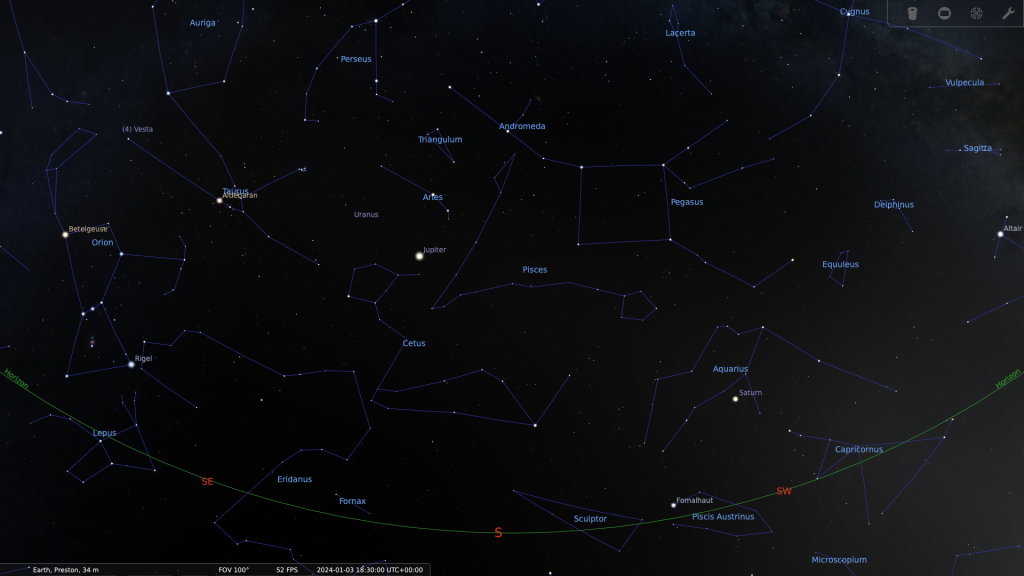

The Sky in January

The first thing to look for is the planet Jupiter high in the sky for most of the night. Look towards the South if you are in the northern hemisphere, look to the North if you are south of the equator. Jupiter will be bright, and pretty unmistakable in the early evening. Look with binoculars, if you have them, to see its moons (and cloud bands, if you’re lucky enough to have access to a telescope).

The ringed planet Saturn is also visible this month, but low in the South-West and fainter. Look with binoculars or a telescope for a view of the impressive ring system. Saturn sets before 9pm and gets earlier as the month goes on, so catch it early if you can. There is also a crescent moon close by on the 14th, with both objects low in the South-Western sky.

If you’re up early, have a look for Venus (easy to spot) and Mercury (quite a lot more difficult!) low in the eastern sky before dawn. Use binoculars for a better chance of spotting the elusive Mercury, BUT DON’T LOOK AT THE SUN with them!

One of the best meteor showers, but one of the least well-observed (thanks to the weather!), is the Quadrantid meteor shower peaking on January 4th. Unlike most meteor showers which originate from comet debris, this one is due to asteroid 2003 EH1 (possibly a dead comet, possibly a rock comet). This asteroid has an orbit around the Sun lasting 5.5 years, only taking it as far out as Saturn, unlike the majority of comets which spend most of their time beyond Pluto. Although the body responsible was only discovered in 2003, the meteor shower has been known about since 1825. The radiant, the position the meteors appear to all come from on the sky, was in the now-defunct constellation of Quadrans Muralis (hence the name) – this location is now part of the constellation of Bootes the Herdsman today.

The Quadrantids can be a very strong shower, with peak rates of more than 100 meteors per hour, but the peak is very short-lived and this year is hampered by daylight during predicted peak hours here in the UK. You have a better chance of seeing good activity from the Americas or Asia this year. Your best chance to view is in the early hours when the radiant is high, after 2am. Sadly the Moon all rises just after midnight and is half illuminated, making viewing fainter meteors more difficult. The short predicted peak of activity is between 0900 and 1500 GMT on January 4th.

The sky later in the year

There will be the usual changing of the constellations as the seasons roll around. Orion is a winter favourite with lots of bright stars and a spectacular star forming region below Orion’s belt that is worth a look with binoculars or a telescope.

There are also a series of meteor showers that happen on the same dates each year as we pass through the debris left behind by comets or asteroids as they orbit the Sun. The ones to watch in 2024, aside from the Quadrantids in January, are the Perseids in mid-August and the Geminids in December. Other meteor showers will happen, but they are not predicted to be as active as these. For most details, keep an eye on the IMO’s Meteor Shower Calendar which is regularly updated.

And a couple of supermoons. While these are not particularly exciting from a scientific point of view, the full Moon is always impressive, and a full Moon at lunar perigee is bigger and brighter than usual, so will be worth a look if the skies are clear. Look up on September 18th and October 17th 2024. (And remember, the astronomical term for this is perigee-syzygy of the Earth-Moon-Sun system. Snappy!)

Spaceflight

2023 was an exciting year for spaceflight and solar system exploration missions, and 2024 is looking like it will be just as exciting. There’s certainly lots planned, both by space agencies like NASA and ESA, governments such as China, and the rapidly growing commercial sector. Here are some things to look out for in 2024.

Europa Clipper is scheduled to launch in October, heading off to survey Jupiter’s moon Europa, an icy world that may support a sub-surface ocean. There is a lot of interest in exploring the potential for habitability of Europa (you need liquid water, the right chemistry, and light/heat) and this probe will help with that by allowing scientists to determine the extent of any sub-surface liquid water and examine the geological processes at work. It won’t arrive until 2030 though, but will complement ESA’s JUICE mission (launched in 2023) nicely when it does.

China plan to launch the next in their series of missions to the Moon with Chang’e 6 heading to the far side of the Moon to attempt the first sample return from the far side of the lunar surface (the side we never see from the Earth). Likely launch in May. We have lunar samples from the near side thanks to Apollo, but not from the far side, so comparing the two will tell us more about the history of the Moon.

June should see the maiden flight of the long-awaited Ariane 6, the European Space Agency’s replacement for the long-serving and highly successful Ariane 5 launch vehicle. It will be able to carry a large payload to orbit, but could lose out commercially to SpaceX’s Starship once that starts flying successfully, and Blue Origin’s New Glenn heavy launcher expecting it’s maiden flight in August. Ariane rockets are expendable, whereas Starship and New Glenn are largely reusable which brings down the cost per launch substantially.

And of course the next Artemis mission taking humans around the Moon for the first time since the Apollo era, pencilled in for November 2024 (but, like all launches, this could slip). Artemis 2 will be the first crewed flight of the Orion capsule, and see the first humans go beyond low Earth orbit since 1972, taking four astronauts around the Moon and back in what is likely to be a highly-watched mission. Expect stunning photographs of the lunar surface!

As well as large programmes like Artemis, NASA have also commissioned a series of commercial companies to provide lunar landers for robotic and autonomous probes through the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) programme. The first of these missions, Peregrine 1, is due to launch on January 8th and will carry two rovers, several sensors, and a collection of time capsules. Several other launches are planned, expanding NASA’s existing work with outside commercial contractors that goes back decades.

We are also likely to see both another record year for satellites launched into low Earth orbit (making the risk of collisions ever more likely, and astronomy more challenging) and more new private operators beginning launch operations, including multiple commercial launches to the Moon, adding further competition to the market.

Biosignatures?

And finally (in Jodcast tradition), there is certainly a lot of interest in looking for evidence of biological processes in space, and it’s possible 2024 might be the year we first find solid evidence of biosignatures somewhere other than the Earth. This could be in samples from Mars, or it could come from further afield in the form of spectroscopic signatures from the atmospheres of exoplanets.

Since the 1990s we have discovered more than 5000 exoplanets around stars other than the Sun. The more we look, the more we find. Remember though that this is still challenging – we had the telescope for almost 400 years before we discovered the first solid evidence for extra-solar planets! And as is usually the case with new discoveries, we found the easier ones first.

Astronomers are using powerful telescopes with very sensitive spectrometers to split up the light coming from the exoplanets. This is challenging because a planet only reflects the light from its host star, rather than emitting its own light, so it is much fainter than the star and much harder to detect (which is why it took almost 400 years to find one!). But if you can do it, and split the light into its constituent colours to make a spectrum, you can then look for the signatures of chemicals in the planet’s atmosphere.

Some chemicals are associated with life, so those are the ones to look for. Many of these chemicals can also be produced by non-biological processes too, so finding a signature in the spectrum is only one part of the puzzle in many cases. But if we find one of them, it will certainly be tantalising.

There are also a lot of astronomers looking for signatures of life in the cosmos using a rather different method. Instead of looking for biosignatures, they are looking for technosignatures – evidence of advanced technology from signals that could not be produced in any natural way. This could be radio signals (like the radio and TV transmissions we have been sending into space for many decades now), or something more advanced such as a powerful beacon, or evidence of megastructures, or even evidence of some cataclysmic event.

It may sound like science fiction, but these are genuine research projects. The probability of finding either a bio- or technosignature may be low, but should we find evidence of life elsewhere in the cosmos, the implications really would be tremendous.

That’s not all folks

There are plenty more exciting events to look out for in 2024, from super moons to comets, results from previous missions, new images from JWST that will be as astonishing as ever, and many, many rocket launches. But it’s lunch time here, so I’ll leave it there for now. If you made it this far, thanks for reading! What are you looking forward to this year?

Recent Comments